Family photographs, land deeds and articles of clothing handsewn in the British-run Ba’quba Refugee Camp near Bagdad are some of the items in “Tell Our Stories: Assyrian Genocide,” the exhibit in Stanislaus State’s University Art Gallery that opens Thursday, June 30 and will have guest speakers Friday and Saturday.

Gallery Designer Dean DeCocker and his team designed the exhibit from hundreds of items curated by the exhibit’s organizers, Stan State Professor Erin Hughes and Kathy Sayad Zatari and Ruth Kambar, both of Assyrian descent. De Cocker’s team will provide support during the live programs planned for Friday, July 1, beginning at 6:30 p.m., and Saturday, July 2, at 1 p.m. Kambar will speak on Saturday. The exhibit runs through Aug. 7, Assyrian Genocide Remembrance Day.

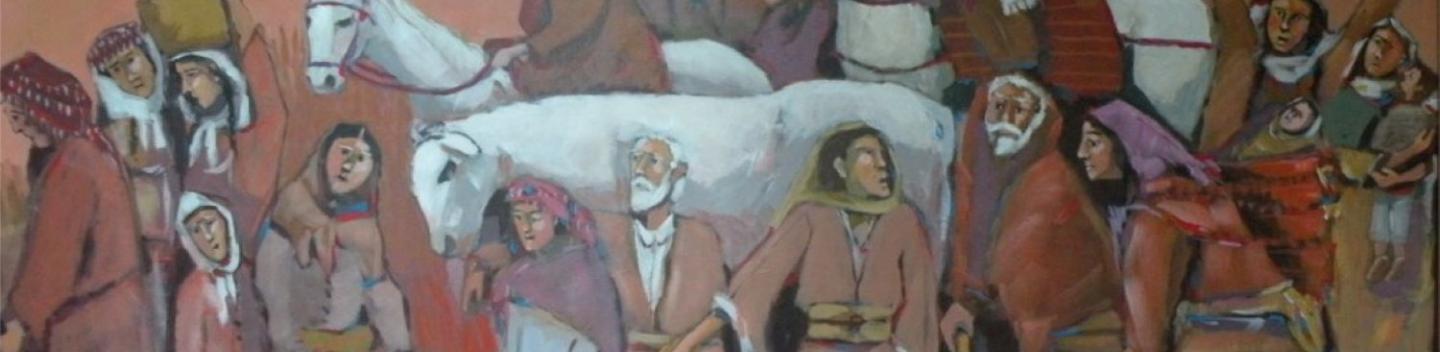

Tell Our Stories: Artifacts from the Assyrian Genocide

Funded by a California Humanities Grant, the exhibit shares through personal accounts and historic records the little-known story of the genocide of Assyrians by Ottoman Turks and Kurds from 1914 to1918. It occurred concurrently with the better-known Armenian genocide.

Two women who learned of their own grandparents’ escape, Sayad Zatari, a Phoenix attorney, and Kambar, a high school and community college English teacher who grew up in Yonkers, N.Y. and studied construction of identity in the Assyrian American diaspora for her Ph.D., each wanted the history preserved. They saw a university as an ideal partner.

Sayad Zatari had shared her grandmother’s escape story with Stan State students, and when she met Kambar through a mutual friend, they agreed the University was ideal.

“They were the drivers of this,” said Hughes, who teaches a modern Assyrian history class and is director of the Modern Assyrian Heritage Project.

She applied for the coveted grant understanding the value of the project to Turlock, where Assyrians first arrived circa 1910.

“Students said their grandparents and great grandparents were in their 80s when they finally started sharing,” Hughes said. “Thank goodness all this history has not been lost.”

Sayad Zatari, 67, didn’t know about her father’s family until she was in her 40s. Her parents divorced when she was a baby, her father died young, and she lived in rural Illinois with her mother’s Irish family.

“In third grade, we went around the class explaining our backgrounds, and I said I was half Irish-half Assyrian. The teacher, Mrs. Miller, told me I couldn’t be, that they were extinct. I must be Middle Eastern or something,” Sayad Zatari said.

That stayed with her and years later, curious about her heritage, she found fellow Assyrians and former Chicago neighbors of her father who helped piece together her story.

Her grandmother’s husband and two young boys were killed, and she made her way from her village in Urmia, in northern Iran, to the refugee camp in Bagdad, carrying with her deeds to the family land. She reached the United States, remarried and started a new life.

Kambar’s grandparents all came from Urmia, too.

“My aunt gave me a change purse and in it there was a little pouch of fabric pinned,” Kambar said. “There’s dirt inside it. My grandmother, at the age of 9, grabbed dirt from home when they were running and that made its way to me.”

A professor from Columbia University taught her the value of oral history and introduced her to recording stories. She sat with her grandfather when he was 90.

“I had this sense of loss of culture that would occur when he left,” Kambar said. “I was worried about that. I started recording. That’s how I learned so much. He was 14. He learned from his older brother’s writings. He said to me, ‘This is who we are. This is what we are.’”

They combined the personal with the historical, collaborating with Hannibal Travis, an attorney and law professor at Florida International University, who is considered the pre-eminent researcher and expert on the Assyrian genocide.

Sayad Zatari, like Kambar, is well connected in the Assyrian community and drew an enormous response when she requested artifacts. She received digital copies of documents, family photos and physical items like a scarf worn by a woman as she fled her village and traveled with her three children during what Assyrians call “Rakka, rakka,” the great running. Some submissions came from as far away as India.

After her father died, a California woman, Annie Elias, found a film in his closet and shared it with Kambar. It was from 1937 and shot by a Chicago man named John Baba, who visited Assyrian communities in various parts of the country at gatherings and social events.

Collectively, the material tells of the genocide and the survivors. And, Hughes said, it tells of resilience.

All materials will be preserved online, and Hughes is accepting more for the digital collection, but gallery space is limited.

Being a part of this exhibit is a learning experience for Hughes, a faculty member since 2019.

“You read a lot of history and hear numbers, and they become numbing and don’t stay with you,” Hughes said. “You hear personal stories, and you can’t forget them. They’re so important because of the power they have to humanize what happened and make you think that could happen to any of us.”