Created by Adrianna Lomas, Black Student Success (BSS) Cultural Resource Specialist, The Blackprint Black History Exhibition preserves and uplifts the stories, histories and contributions of Black students, leaders and communities connected to Stanislaus State and the Central Valley. This living archive highlights moments of achievement, leadership and resilience—centering Black excellence in higher education and honoring the lasting impact of those who have shaped campus life and student success.

Black Life in the Central Valley: Black Migration

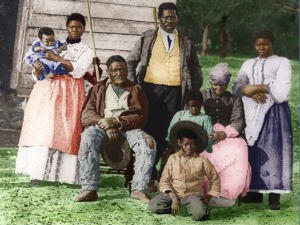

Since the ending of American Chattel slavery in 1865 Black Americans have migrated throughout America for safety and opportunity multiple times. There have been four recorded waves of Black migration post-slavery

During and after slavery many Black people in the South moved northward to escape slavery, racial violence and economic oppression. This early migration laid the foundation for future movements toward freedom and self-determination.

(Library of Congress)

Known as the Great Migration this period saw millions of Black Americans leaving the rural South for Northern industrial cities such as Chicago, Detroit and New York. They sought better jobs, education and political rights, reshaping the cultural and social landscape of urban America.

(Library of Congress)

By the 1970s migration patterns shifted again. Black families moved into urban centers for better employment opportunities and access to emerging Black middle-class neighborhoods. This era emphasized progress, visibility and upward mobility within American cities.

(Public Domain Image Archive)

The current wave represents a reversal of earlier trends. As gentrification reshapes major cities rising costs and displacement have pushed many Black residents out of traditional urban hubs like San Francisco, Oakland and Hayward. Many have moved to more affordable areas such as Stockton, Modesto and Sacramento in California’s Central Valley seeking safer neighborhoods and attainable home ownership.

(The Stockton Record)

Impact on the Central Valley

This migration has reshaped the demographics of the region. While the overall Black population in the Central Valley remains relatively small, cities like Stockton and Sacramento now serve as modern migration destinations for Black families. These shifts reveal systemic factors of economic inequality, housing policies and urban redevelopment. these factors continue to influence where Black Americans can live and thrive.

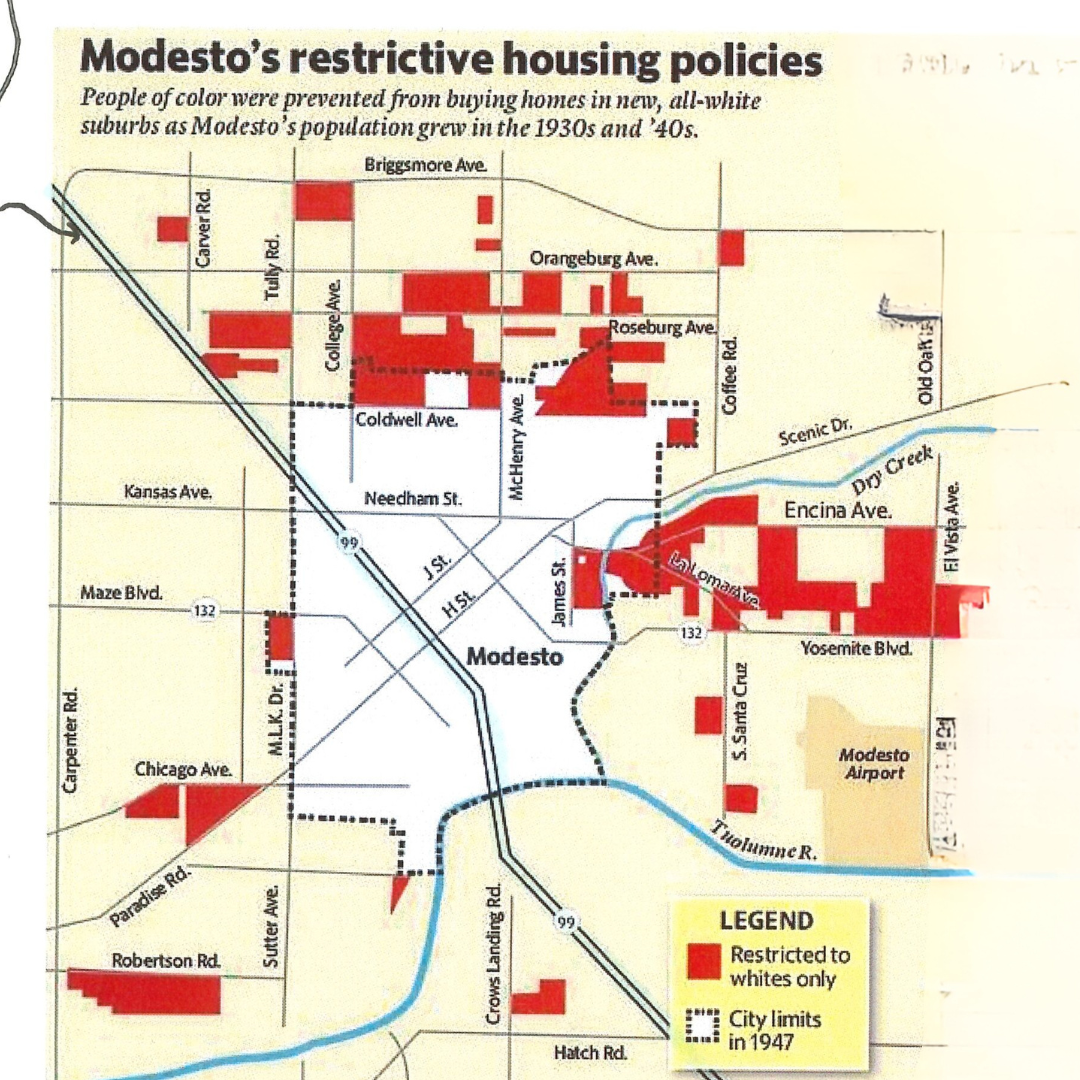

Redlining and Housing Discrimination

Throughout the early to mid-20th century the United States practiced a policy known as redlining. A form of systemic housing discrimination that shaped the racial and economic layout of American cities. Redlining was a discriminatory practice where banks, insurers and governments denied loans or services to residents in certain neighborhoods often based solely on race.

As a result these communities were often pushed into low-income neighborhoods that experienced:

- Poor-quality housing

- Lack of investment and maintenance from local governments

- Proximity to industrial sites and pollutants resulting in environmental racism

- Although redlining is now illegal its long-lasting effects are still visible across America in patterns of segregation, income inequality and environmental injustice.

The Lasting Effects of Displacement and Environmental Injustice

These policies also created patterns of environmental racism. During freeway expansion projects, including the construction of Highway 99, the state displaced many Black and Brown families from their neighborhoods. Many were relocated to Monterey Tract Park near Ceres, a rural area in Stanislaus County’s dairy region. The land was poorly maintained, underfunded, and often unsafe, with issues like contaminated groundwater and unstable soil making homebuilding difficult.

Economic barriers deepened these inequalities. In “Image of a Black Father,” Charlie Crane described his experience moving to Modesto in the 1960s. He recalled that Black residents were restricted to living on the West Side and faced job discrimination. Most local companies refused to hire Black workers. Campbell’s Soup Factory became the first major employ Black people in 1963.

The effects of these policies are still visible today. Modesto’s smaller Black population and lower visibility are not accidental but the result of systemic and intentional exclusion that shaped where people could live and work. The city’s racial geography, housing patterns, and economic disparities stand as living reminders of this history proof that, as the saying goes, “history isn’t the past we are currently living in it.”

Civil Rights Activism in Stockton, California

The Central Valley’s agricultural and social history has long been shaped by communities of color. From the 1940s through the early 1960s, much of the region’s farm labor force consisted of Black Americans and poor white migrants who arrived after the Dust Bowl, followed by a growing number of Mexican and Central American laborers by the mid-20th century.

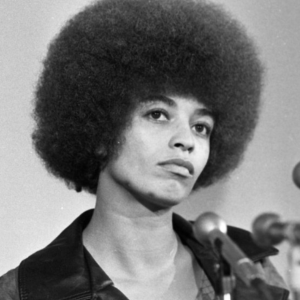

In the 1960s, national civil rights events such as “Bloody Sunday” in Selma and the Watts Riots galvanized activism in Stockton, where residents marched in solidarity and organized for change. Local leaders, including Reverend Robert L. Phillips, convened public forums calling for job training, community centers and action against racial inequality.

This momentum extended to the University of the Pacific, where Morris Chapel became a space for open dialogue and hosted influential civil rights leaders, including Angela Davis—pictured right—and Huey Newton. In 1969, UOP launched the Community Involvement Program (CIP) to support low-income and minority students through scholarships, tutoring, and mentorship, producing notable alumni and reflecting the lasting impact of 1960s activism on education, empowerment, and equity in the Central Valley.

Seeing Everyone: Building Community

In California’s Central Valley, people of color often navigate subtle yet persistent forms of bias that shape daily life, from public spaces to workplaces. Experiences like these, shared by members of local communities, reflect the lasting impact of historical stereotypes and misrepresentation. Promoting true multicultural harmony means more than celebrating diversity—it requires actively creating inclusive spaces where all residents feel seen, valued, and respected, and where the voices of those who face these challenges help guide the way toward understanding and equity. (Diversity: Minorities Suggest Ways to Promote Multicultural Harmony).

Black Voices, Presence and Legacy at Stan State

Dr. Fred Edmondson

In March 2000, The Signal featured an article on V.P. Fred Edmondson, who had been working at Stanislaus State for 21 years at the time. His career began as a recruiter for the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) before he was promoted to Director of Counseling Services. He later became Assistant Vice President of Educational Services and eventually rose to Senior Director and Vice President of Student Life.

As Vice President of Student Life, Edmondson oversaw several key areas of campus life including Housing and Residential Life, Student Health Services, Associated Students Inc. (ASI), the University Student Union, and the Student Activities Center. He also managed Judicial Affairs and Student Discipline, Student Affairs Administration, budget planning and personnel, and Student Leadership and Development Programs.

Edmondson earned a Doctorate in Higher Education Administration from the University of the Pacific, a Master’s in Counseling and Psychology, and a Bachelor’s in Physical Education. His early work experience included hoeing beets in the fields and working at the Campbell’s Soup Factory one of the first companies in the Central Valley to employ Black workers. Before coming to Stanislaus State, he served as the Director of Psychological Services at the University of Rochester.

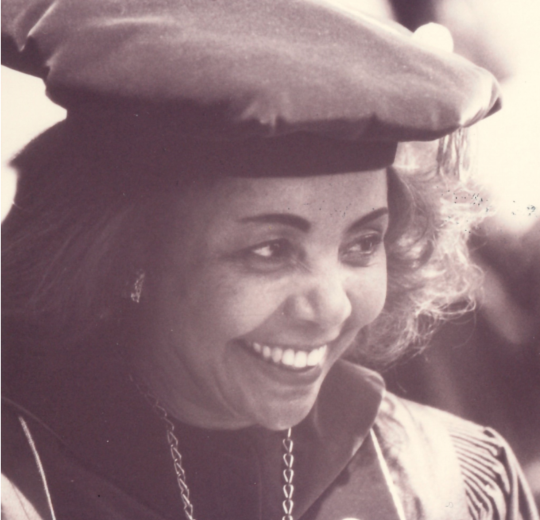

Dr. Marvalene Hughes

Dr. Marvalene Hughes was a pioneering leader in higher education whose career has helped redefine student support, leadership and access nationwide. In 1995, she was featured in Ebony magazine for her role in advancing Black women into senior academic leadership, highlighting Black women as one of the most highly educated populations in the country.

She served as the sixth President of Stanislaus State from 1994 to 2005, leading the university through a period of remarkable growth and transformation that strengthened its academic foundation and expanded access for students across the Central Valley. During her tenure, Stan State’s enrollment doubled to more than 7,800 students, reflecting the University’s growing reach and impact.

Under her leadership, the Stockton Campus moved to its permanent home at University Park, and the Turlock campus added more than $135 million in new buildings and facilities. These developments included four scenic lakes that—together with the President Emerita Marvalene Hughes University Reflecting Pond—form the University’s 12-million-gallon landscape water management system, now a defining and beloved feature of the campus.

Dr. Hughes earned her undergraduate and graduate degrees from Tuskegee University and, in 1969, became the first Black person to earn a doctoral degree from Florida State University in Counseling and Administration. Throughout her career, she held senior leadership roles at institutions including the University of Minnesota, the University of Toledo, Arizona State University, and San Diego State University, where she helped shape modern student affairs, expanded counseling and support services and mentored future educators and administrators.

Black Student Success as an Initiative

Black Student Success is housed within the Warrior Cross Cultural Center under Student Leadership, Engagement and Belonging.

Black Student Success is part of a California State University systemwide initiative focused on outreach, recruitment, enrollment persistence, graduation and success of Black students across all CSU campuses. The program works to create a supportive environment where Black students can thrive academically, socially and culturally.

Myisha Butler-Ibawi

Associate Director of Student Success Initiatives | President of Black Faculty & Staff Association

“My role is to create inclusive and affirming spaces that celebrate and uplift our students. I work closely with students through one-on-one support to promote wellness, academic success and personal growth, while also helping them navigate and connect to campus resources that support their goals. My focus is on ensuring students feel seen and empowered throughout their academic journey.”

Featured Newsletters

The featured newsletters below were created by Adrianna Lomas for Black Student Success, showcasing thoughtful storytelling, design and community-centered messaging.

Contributions & Collected Works

- CalMatters: California’s Black population exodus - July 15, 2020

- Civil Mirror: Where are all of the Black people in Modesto, California? - September 27, 2022

- Eissinger, Michael: Obscured by the Tule Fog: Rural African Americans fade into the San Joaquin Valley, Conference paper

- KQED: Black farmworkers in the Central Valley: Escaping Jim Crow for a subtler kind of racism - December 4, 2019

- Modesto Bee: Diversity: Minorities suggest ways to promote multicultural harmony - September 3, 1990

- San Francisco State University: Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development - July 18, 2007

- Stanislaus County Planning Commission agenda (PC-407–PC-448) - August 4, 2016

- StoryMaps: Black history and geography [Interactive map] - December 20, 2021

- StoryMaps: Exclusionary spaces in Stockton [Interactive map] - May 7, 2021

- University Library, California State University, Stanislaus: The Signal article - March 8, 2000

- Visit Stockton: Stockton, California’s civil rights movement: A trip through time - February 4, 2025

Updated: February 05, 2026