Noble Dinse left the world a little more beautiful when he passed away earlier this year at the age of 79.

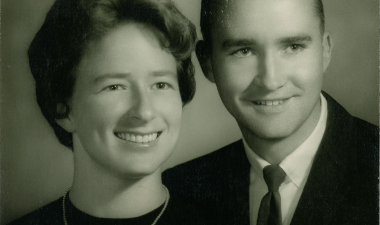

A set designer who helped launch the careers of countless Stanislaus State students, Noble was a professor in the Department of Theatre for 37 years, from 1970-2007, and lent his artistic flair to numerous department productions. He and his wife, Sandra, also founded Playhouse Merced in 1994 (originally the Merced Center for the Performing Arts), and he designed sets and backdrops for productions at Sierra Repertory Theatre in Sonora and Columbia, as well as Sacramento’s Music Circus.

“Noble was good about bringing students along whenever he was working professionally,” said Carin Heidelbach, associate professor of Theatre and current department chair, who began at Stan State as a student in 1987. “We all interned when he was working at Music Circus in Sacramento. We had professional experience as students.”

Dinse’s generosity and encouragement to his students to learn the craft of backstage work did more than create dazzling sets and backdrops. In some cases, it changed their career trajectories.

“I thought I was going to be an actor when I came as a student in 1988,” said former student and retired Stan State professor Clay Everett. “When I got to the University, I saw Noble’s office and worksite, and I started changing my mind.”

Dinse’s office was set up with stations for drawing designs and building scale models. Shelves around the space lined with models he created for previous shows.

Beyond his office, Dinse established the scene shop for building sets and painting backdrops for the burgeoning Department of Theatre. The shop remains largely as he left it — a creative training ground for students.

It was a place where actors like Everett enjoyed fresh experiences, learning invaluable lessons about the work that goes on behind the scenes of a live performance.

“I don’t know if I would have become a director if not for working with Noble on design,” Heidelbach said. “I was all about acting. I changed direction in grad school, thinking about what Noble did for me. Without him, I wouldn’t know how to paint. There are so many things you take for granted when you’re acting. I was an assistant designer. He taught me to paint the floor and sets. Working on sets, you make choices, and it made me think of a play as something bigger than a character. That was a big deal.”

Everett was like Heidelbach as far as thinking he would make a living as an actor.

He arrived at Stan State having been a welder and sheet metal worker in the military before building tanks and trailers for a local company after he was discharged.

“I fell in love with design and tech and realized I’d been trying to get away from it,” Everett said. “I had a lot of construction under my belt already. When I saw his office, things started clicking. I changed over and became his assistant.

“It was the organization, the way he had it set up. Noble was a set designer, so he had a drawing station with all the tools you needed. There was a model construction area with all the tools for that. Models he made for other shows were displayed on upper shelves. It was just a magical thing for me. I loved walking into his office and seeing the process at every station. For a craftsperson, this was heaven.”

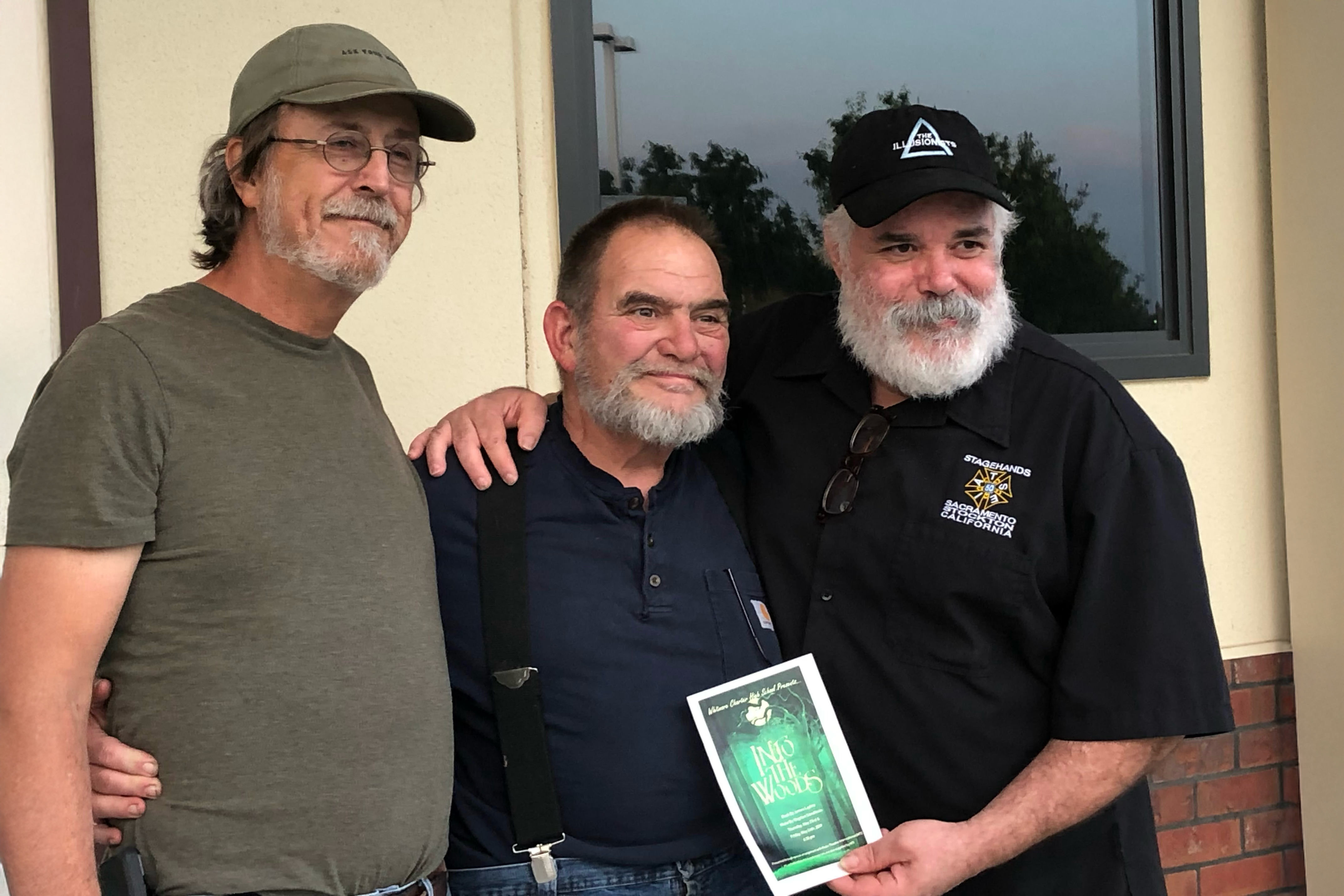

Dinse became a mentor, and Everett spent four years as his assistant at Music Circus. Later, after Everett completed his master’s degree and was teaching at Willamette University in Salem, Ore., Dinse encouraged him to return to Stan State in 2002 in the newly created position of lighting designer and technical director.

For five years, the former student worked side-by-side on Stan State productions with his mentor and the man who would become his best friend. Everett even named his son Noble.

“Noble designed the shop we have,” Heidelbach said. “It’s the only shop on campus where you paint, do woodwork and can see experienced welders' work. A lot of students flock to it.”

Learning about the part of theatre that most appealed to Dinse is a theatre major’s requirement.

“What I think is great about Stan State as department chair is performance majors have a really good sense of all the work that goes into getting them lit and for the mic to work,” Heidelbach said. “The world they exist in as their character needs all that really important work. Performance and the tech side are dependent on each other. I learned that from Noble.

“The vast majority of students who come into Stan State as first-year students aren’t thinking about those outside things, about what’s happening in the wings and what goes into the prep before they can perform. That's the nuts and bolts of our program. They have to do everything at least once, not just act. They have to be a stage manager and do the prep. Noble was one of the original professors to build the program.”

For Dinse, there was joy in creating the art behind the performance, a skill he mastered, Heidelbach and Everett said.

“Noble was a fantastic designer,” Everett said. “I remember one time I said, ‘Noble, that took you five minutes to do.’ He said, ‘No, it took me 35 years and five minutes.’”

He never stopped learning and never stopped creating. While he was creating sets at Stan State and elsewhere, he had exhibits of his acrylic paintings. Later in life, he produced sculptures.

Dinse remained in contact with the Stan State Department of Theatre, Heidelbach said, visiting or just staying in touch with his former students. He was patient with them when they were students, stopping to answer questions as he taught by putting them to work. And he remained a friend and mentor after they’d graduated, leaving a legacy that lives on in the program he helped build and the countless lives he shaped.