When Dr. Michael L. Brodie agreed to serve as the physician in Stanislaus State’s Student Health Center from the mid-1990s until the early 2000s, he brought his own style.

It wasn’t just that he was the first Black physician to serve in that role. He went beyond providing medical care.

Brodie, who recently passed away at 79, took time to get to know the students he served and helped them steer their course.

“One thing I did hear from students at that time or down the road is that my dad would often have a conversation with students,” said his daughter, Kilolo Brodie-Crumsey, a professor in the Department of Social Work. “Yes, they would come in for a health-related issue, but he’d be talking to them about what their major was, what classes they were taking and what they were going to do when they graduated. They got their medical needs addressed, but he was always going to ask you, ‘What are you working on in school? What are you doing next [academically]? ‘How are you doing?’ You couldn’t get away from it.”

That was the kind of physician he was.

From the time he graduated from UC Davis School of Medicine and began practicing pediatrics in 1976 in Los Angeles, Brodie considered more than the physical health of a person.

“I think back to when I was in junior high and high school, and my friends would call on the phone,” Brodie-Crumsey said. “Before he’d hand me the phone, he’d have a conversation with them. ‘How are you doing?’ ‘What have you been up to?’ He’d weave it in. It was casual, but there was going to be a dialogue with them before he even told me I had a phone call waiting.

“When my friends would visit, they wouldn’t be nervous about my dad asking them questions. It was the opposite. They liked to pick up where they left off. They’d give a report back. It was done in such a way that you didn’t feel like you were being grilled, but someone was interested in your future. Students and friends of mine would be excited to come back and fill him in or update him on what shad happened since their last conversation.”

She laughs at the memory and realizes it has impacted her own work.

She stopped to visit with a student after class who’d recently had a baby. After looking at photos of the baby and asking how she was doing, Brodie-Crumsey found herself advising her student about future educational steps that might be possible for a young mother.

“It was in that moment that I could see my dad in me, where I was interested in how she was doing and managing with a newborn, but somehow, I shifted the conversation, organically, to what’s next,” Brodie-Crumsey said. “That social work element, I always thought I got it from my mom. But as I got older and was living here in this town with him all these years, I watched him. It’s surprising. I’m more like him than I thought I was. It is a gift.”

Brodie moved from Los Angeles to Turlock in 1993 when he learned of the shortage of physicians in this region and became the city’s first Black doctor. His daughter chose to live with him after she earned an undergraduate degree in psychology from Clark Atlanta University in 1994.

She and her brother had lived with her mom and spent weekends with their dad, but Brodie-Crumsey decided it was time to give her mom a break from caring for them.

She was surprised to find a California State University in Turlock, and her dad informed her that she’d be going to school there. Brodie-Crumsey took a variety of post-graduate courses before discovering the Master of Social Work program, from which she graduated in 1998.

During her years on campus, her father treated her fellow students while maintaining a general practitioner’s office in Turlock.

She was not one of his patients.

“No, he was never my doctor,” she said. “I wasn’t going to see him (on campus). That was my personal, private business. We always kept boundaries.”

Still, her love and respect for her father are evident in the way she speaks of his career.

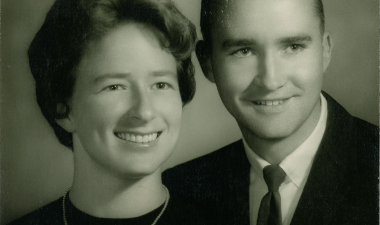

Born in Baltimore, , he served in combat in Vietnam with the U.S. Marines at age 18. He attended Morgan State University and UC Berkeley before graduating from UC Davis School of Medicine.

He left his practice in Los Angeles for Turlock, and it wasn’t long before Stan State Associate Vice President and Dean of Students Fred Edmondson asked him to work in the Student Health Center.

After leaving the University, Brodie spent the rest of his career working in geriatric medicine and was the medical director of several skilled nursing facilities. He and his wife, a registered nurse, volunteered for several decades in the Philippines. When he retired, they moved to her native country. He was there, with his wife at his side, when he passed away.

Although Brodie-Crumsey once thought of following in her father’s medical footsteps, she admits with a laugh that her plan was dashed during her first year of college when she struggled through biology.

She realized, though, that she has carried on some of his legacy.

“Once I got my Master of Social Work and started working with people in communities, I realized I had academic social work training, but the other piece came from watching my dad, learning how to have a conversation with someone where you don’t come across as off-putting or demanding but instead as genuinely showing interest in people.”

More than 300 people appreciated how he showed an interest in them and attended Brodie’s memorial service. Brodie-Crumsey wants to keep his legacy alive and has established the Dr. Michael L. Brodie Memorial Fund for a future scholarship for anyone who wishes to donate.