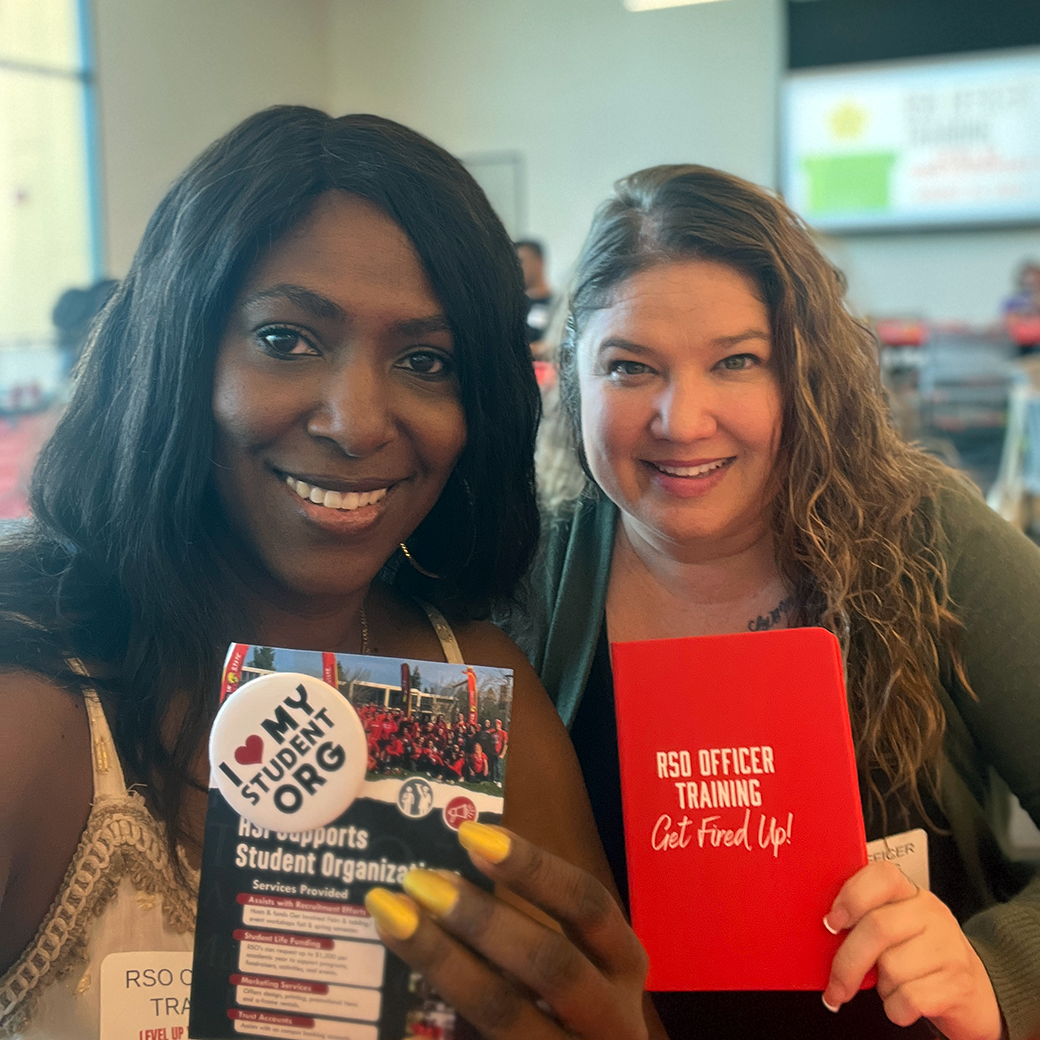

Tasha Wilson and Jessica Balli aren’t fresh-out-of-high-school college students, but they have the same enthusiasm as their younger classmates.

The two, best friends for some 20 years, started at Stanislaus State in spring 2024, plan to graduate in spring 2025 and have lots of work to do before they cross that commencement stage.

Wilson, a sociology major who wants to become a college professor, and Balli, a psychology major with dreams of being a counselor at juvenile detention facilities, are founding officers of Stan State’s Collegiate Recovery Community, a new student organization started by Counseling and Psychological Services counselor Ruthie Torres.

Not only are the two friends officers, but they are also among 40 students nationwide selected for the Collegiate Recovery Learning Academy (CRLA). They attended a weekend conference in Washington, D.C., in November.

Neither expected to be part of the fellowship program for students passionate about the intersection of addiction and mental health recovery, leadership and advocacy when they penned essays for their applications.

“My goal is to destigmatize the way people with addiction are looked at,” said Wilson, the president of Stan State’s organization and a Stanislaus County Behavioral Health employee who counsels 18-to-25-year-olds with addiction issues. “They’re frowned upon. I wrote in my essay about how to make students and community members aware that this is a disease. We should help them find the tools to get through it the best they can.”

Balli, the organization’s treasurer, wrote from personal experience.

“I had a couple family members struggle with addiction and mental illness,” Balli said. “I have young kids who will, hopefully, go to college someday. It’s something that needs to be out there on college campuses. My vision is providing awareness on campus and a safe space for students to go to talk about it. If there’s one person we can reach and help, I’ll feel like we’ve won.”

Being a part of CRLA, the two said, will teach them about organizing the Stan State group and provide tools and tips to raise awareness and help students.

“My hope is we’ll be able to leave something monumental so people who follow us will remember Jessica and Tasha started this off,” said Wilson. “That’s my goal, to do something fantastic while we’re here, to leave a lasting memory that two women, who are best friends, started an organization that took off and changed that stigma attached to people with addiction.”

When Ruthie Torres first arrived at Stan State in 2022 as a Counseling and Psychological Services counselor, Dean of Students Heather Dunn Carlton asked her to lead a committee to update the University’s drug and alcohol policies, which hadn’t been revised since 2007.

From there, Torres, whose specialty is addiction recovery, began planning a community committed to clean and sober living, enlisting Wilson, whom she’d known as a student working under her at Modesto Junior College, Balli and Maximo Madrigal as organization’s events coordinator to serve as student leaders.

Her work is personal.

Pregnant at age 16 and a divorced mother of a 3- and 8-year-old at 25, Torres began a three-year struggle with methamphetamine addiction.

“One day I woke up and said, ‘This is not you. This is not what you intended for yourself. This is not going to continue.’”

She quit cold turkey and said she hasn’t used anything again.

Now remarried with a blended family of seven children, Torres arrived at Stan State after working for a private agency helping those with opioid addictions and then at Stanislaus County Behavioral Health, determining treatment for incoming mental health patients.

The desire to help others began when she was 6, and her best friend was her uncle, who was four years older and born with a rare genetic disease called mucopolysaccharidoses, which causes dwarfism and mental impairment.

“I saw firsthand stigmatization, marginalization, bias,” Torres said. “I saw what it did to my uncle and to me, and even the self-stigmatization by families of those with severe mental illness.

“By the time I was in sixth grade, I had a goal of going to school to become a doctor of psychiatry.”

Her teenage pregnancy halted her plans, but at 36, she began pursuing that childhood dream. She enrolled at Modesto Junior College, and thinking she couldn’t get into Stan State, enrolled at Brandman University, where she earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Now, she’s set on making a difference at Stan State with the Collegiate Recovery Community.

“If it could be what I want it to be, it could take 10 years,” Torres said. “What I do expect is immediate service from our students through a recovery ally program that’s already established.”

She’s training allies and will teach CRC members to lead the one-hour training for faculty, staff and campus leaders. Those who complete the training will receive a pin to wear, signaling to students someone is trained to help them if they’re struggling.

Sign-ups for training sessions are available on the CAPS website.

CRC members are working to become mentors for junior high and high school students associated with Prodigal Sons and Daughters, a Turlock non-profit dedicated to helping families touched by addiction.

Another one of Torres’ plans is advocating for a “sacred space” in the new housing building under construction, which could be used for affinity groups, as a prayer space and for the Collegiate Recovery Community to have meetings and sober activities or events. For now, the group has no meeting space.

Getting the word out about the new organization has been a challenge, but Torres and her officers are enthusiastic to put in the work. They see it as crucial.

“Because we’re a small rural college without a football team, I’ve heard people say we don’t have that problem on this campus,” Torres said. “This is the highest group of individuals in America who are at risk for using and having that problem. I don’t see how you could think we don’t have that problem.”

There’s work to be done, but it starts with a mission to be a “community made up of individuals who identify as being in recovery from drug or alcohol addiction or just leading a sober lifestyle,” Torres said.

In addition, CRC wants to help the rest of the student body, whether they are struggling with addiction, in recovery and in need of a safe harbor on campus or wanting to be a recovery ally.

“Our main goal is just to create a recovery culture on campus,” Torres said.